How Google’s MapTrace research reveals a broader revolution in spatial intelligence, and why local and state government GIS programs need to start preparing now.

Look at a map of your city — the parcels, the streets, the zoning boundaries layered over floodplains and utility networks. Within seconds, your brain processes the spatial relationships between these features. You understand that roads connect intersections, that parcels have boundaries you can’t walk through, and that a path from City Hall to the water treatment plant follows a specific, constrained route. This kind of spatial reasoning is so fundamental to human cognition that we rarely think about it.

Artificial intelligence, for all its remarkable advances, has struggled with exactly this skill. Until now.

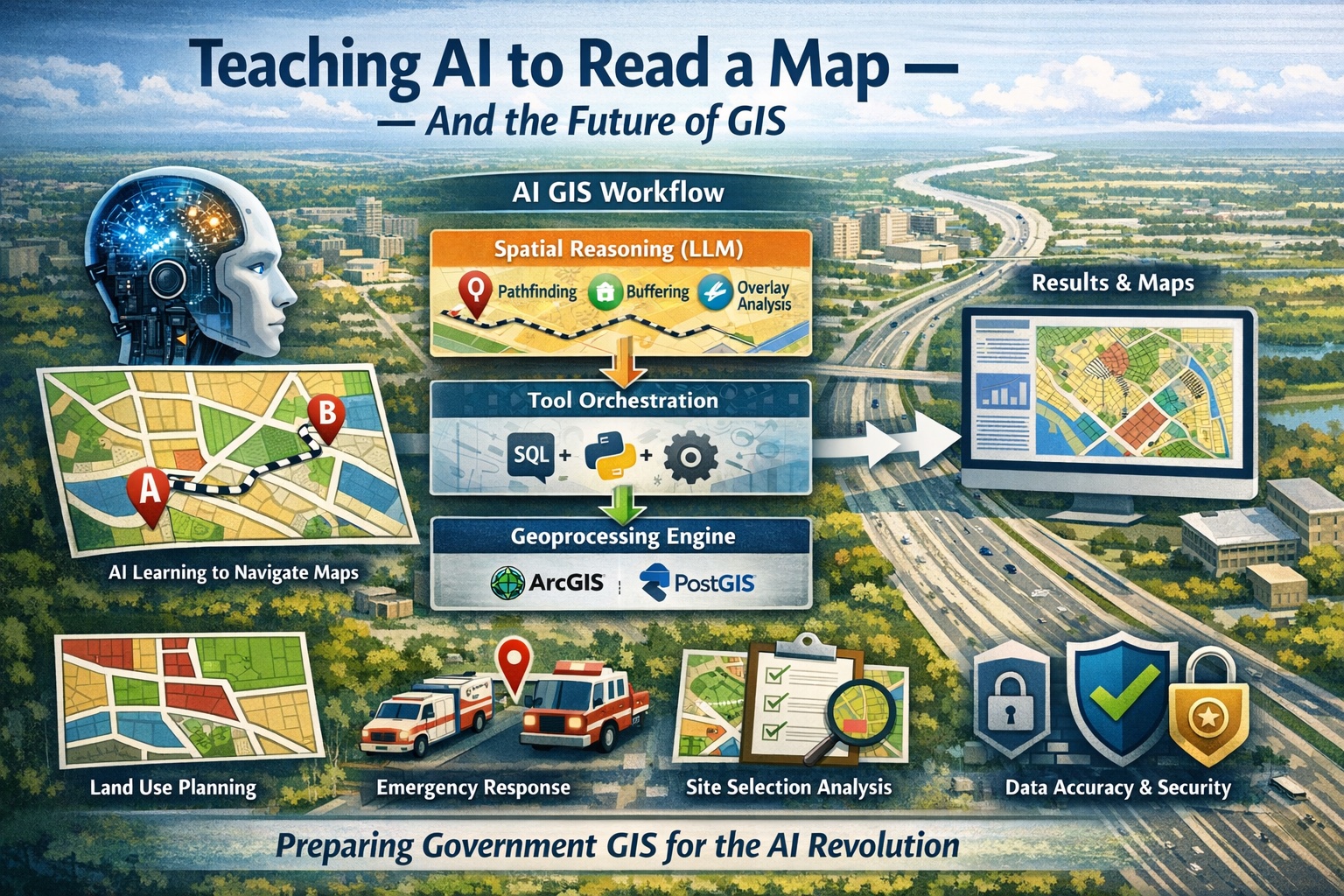

On February 17, 2026, Google Research published “Teaching AI to Read a Map,” a blog post introducing their new MapTrace system for teaching multimodal large language models (MLLMs) to trace valid routes on maps. On its surface, the research addresses a narrow problem — path-finding on visual maps. But beneath that surface lies a breakthrough methodology with profound implications for the entire geospatial industry, and particularly for the local and state government agencies that depend on GIS to manage everything from emergency response to land use planning.

What Google Actually Built

The core challenge MapTrace addresses is deceptively simple: can an AI model look at a map image and trace a valid path between two points? Not a straight line through buildings and walls, but an actual navigable route that respects the physical constraints of the environment.

Today’s multimodal large language models — systems like Gemini, GPT-4, and Claude that can process both images and text — are remarkably good at identifying what’s in an image. Show them a map of a zoo, and they can tell you it’s a zoo. They can list the animals you might find there. But ask them to trace a valid walking path from the entrance to the reptile house, and they fall apart. They might draw a line straight through an enclosure or a gift shop, failing to understand the basic spatial constraints that any five-year-old grasps intuitively.

This gap exists because these models learn from images and text — they learn to associate the word “path” with pictures of sidewalks and trails. But they rarely encounter training data that explicitly teaches the rules of navigation: that paths have connectivity, that you can’t walk through walls, and that a route is an ordered sequence of connected points.

The most obvious solution — collecting millions of maps with paths traced by human annotators — is prohibitively expensive and practically impossible to scale. Many of the most useful complex maps, such as those for shopping malls, museums, and theme parks, are proprietary and unavailable for research.

MapTrace solves this with an elegant, fully automated pipeline that uses AI to generate its own training data in four stages:

First, a large language model generates diverse text prompts describing maps — everything from “a zoo with interconnected habitats” to “a shopping mall with a central food court” — and a text-to-image model renders them into complex map images.

Second, the system identifies all “walkable” areas within each map by clustering pixels by color. Another AI model serves as a “Mask Critic,” examining each candidate mask and judging whether it represents a realistic network of paths.

Third, the validated walkable areas are converted into a structured graph — essentially a digital road network where intersections become nodes and connections become edges.

Fourth, classic shortest-path algorithms (Dijkstra’s) generate routes between random points on the graph, and another AI “Path Critic” performs a final quality check, ensuring each route is logical and stays within the lines.

This pipeline produced a dataset of two million annotated map images with valid paths, which Google has open-sourced on HuggingFace.

The results are striking. When researchers fine-tuned Google’s Gemini 2.5 Flash model on just 23,000 of these synthetic paths, the model’s path-tracing error dropped significantly. More importantly, the models became far more reliable — the percentage of time they could produce a valid, parsable path increased across all tested models. The fine-tuned Gemma 3 27B model saw a 6.4 percentage point increase in its success rate.

The central finding confirms what the researchers hypothesized: fine-grained spatial reasoning is not an innate property of large language models. It is an acquired skill — one that can be explicitly taught through targeted, synthetically generated training data.

Why This Matters Beyond Route Tracing

MapTrace’s significance extends far beyond teaching an AI to navigate a theme park map. The methodology — generating synthetic spatial training data to teach models specific spatial reasoning skills — demonstrates a template that could be applied across a wide range of GIS operations. It does not, on its own, solve the full breadth of spatial reasoning challenges. But it establishes a scalable, repeatable approach that future efforts can build on.

Consider the traditional GIS functions that local and state governments rely on daily:

Spatial relationships and topology — understanding adjacency, containment, intersection, and connectivity between geographic features. Benchmarking studies such as GeoBenchX and GeoAnalystBench have shown that even advanced models frequently struggle with coordinate system interpretation and geometric precision tasks, including incorrectly computing distances and areas using geographic coordinate systems instead of projected systems. A MapTrace-style pipeline could generate synthetic examples teaching models about polygon adjacency, line-polygon intersection, and point-in-polygon relationships.

Coordinate systems and projections — the perennial source of errors in GIS work. Models routinely confuse geographic and projected coordinate systems, a mistake that can produce wildly incorrect measurements. Synthetic training data showing the same geometries in different coordinate reference systems, paired with measurement tasks, could teach models when and why projection matters.

Buffer analysis, overlay operations, and spatial joins — the daily bread and butter of government GIS analysts. These operations require understanding geometric transformations, not just pattern recognition. Synthetic datasets showing inputs and outputs of buffers at various distances, union and intersection operations on overlapping polygons, and spatial join logic could build this capability incrementally.

Network analysis — MapTrace already touches on routing, but the broader domain includes service area analysis, closest facility calculations, and origin-destination matrices that governments use for everything from emergency response planning to school district optimization.

Site selection and suitability analysis — perhaps the most valuable and most challenging application, because it requires chaining multiple spatial operations together in sequence. Current benchmarking research consistently identifies these multi-step spatial reasoning tasks as the most difficult for all models.

It’s important to note that the future of AI in GIS will not rely solely on synthetic spatial training data at massive scale. The path forward will likely combine synthetic training (as MapTrace demonstrates), tool-calling capabilities (where models invoke existing geoprocessing engines), and retrieval-augmented execution (where models access documentation, schemas, and domain knowledge at runtime). MapTrace is best understood as a proof of concept for one critical piece of that puzzle.

Two Competing Paradigms — And Why Both Matter

As research accelerates at the intersection of AI and geospatial science, two fundamentally different paradigms are emerging for how LLMs will interact with spatial data. Understanding the distinction between them is essential for anyone trying to anticipate where GIS is heading — because each paradigm has different strengths, different limitations, and different implications for how government agencies will eventually use these tools.

Paradigm 1: Teaching Models to Reason Spatially

The first paradigm, exemplified by MapTrace, focuses on training AI models to internalize spatial concepts directly — to develop something resembling genuine spatial cognition. Rather than telling the model how to solve a spatial problem step by step, this approach teaches the model to understand spatial relationships well enough to reason about them independently.

MapTrace demonstrates this by fine-tuning models on synthetic examples of valid paths until the model learns, at some level, what makes a path valid — that routes follow connected walkable areas, that you can’t pass through solid obstacles, that paths have directionality and sequence. The model isn’t executing Dijkstra’s algorithm at inference time. It has absorbed enough examples of correct spatial reasoning that it can generalize to new maps it has never seen.

Extrapolate this approach across GIS, and you can imagine models trained on synthetic datasets for each major category of spatial reasoning. Millions of examples teaching topology — here’s a polygon that contains another polygon, here’s one that’s adjacent, here’s one that intersects. Millions of examples teaching coordinate system behavior — here’s why the same geometry produces different area measurements in WGS 84 versus a State Plane projection. Millions of examples teaching overlay logic — here’s what happens when you intersect these two polygon layers, and here’s the resulting geometry.

The appeal of this paradigm is its potential for generalization. A model that truly understands spatial containment doesn’t need to be told which geoprocessing tool to use — it understands the concept and can apply it flexibly across different contexts, data types, and representations. It could look at a satellite image and reason about what it sees spatially, not just classify objects.

But the limitations are significant — and for government GIS applications, they are critical. An LLM may approximate geometric relationships, but computational geometry engines operate on exact vertex math. That distinction matters when acreage determines tax assessments, when setback distances determine building permit eligibility, or when buffer boundaries determine which property owners receive legal notification of a public hearing. No amount of training examples will make an LLM as numerically precise as a dedicated geometry engine like the one inside ArcGIS or PostGIS. LLMs will not replace these engines. They will interface with them.

There’s also a scalability question: the MapTrace team generated two million training examples just for route tracing. Covering the full breadth of GIS operations through synthetic spatial training data would be an enormous undertaking — though it’s worth noting that different spatial skills may require different volumes of training data, and that synthetic generation pipelines like MapTrace’s can be adapted and reused across domains.

Research efforts aligned with this paradigm include the SpatialBench framework, which decomposes spatial cognition into five progressive levels — observation, topology and relation, symbolic reasoning, causality, and planning — providing a structured way to evaluate and incrementally improve model capabilities. The broader field of evaluating LLMs’ spatial cognition in a GIScience context is also growing, with studies revealing that while models perform reasonably well on memory-based geographic tasks, they face significant challenges in reasoning-based tasks that require contextual deduction and spatial analysis.

Paradigm 2: Teaching Models to Orchestrate GIS Tools

The second paradigm takes a fundamentally different approach. Instead of teaching the model to be a spatial reasoning engine, it teaches the model to use existing spatial reasoning engines — to act as an intelligent orchestrator that understands which GIS tools exist, when each is appropriate, what parameters they require, and how to chain them into multi-step workflows.

This is where the majority of active research and development is concentrated today. The concept is straightforward: an LLM receives a natural language request (“identify all parcels within 500 feet of a floodplain that are zoned commercial”), decomposes it into a sequence of GIS operations (select floodplain features → buffer by 500 feet → spatial join with parcels → filter by zoning attribute), generates the code or API calls to execute each step, and assembles the results.

Google’s Geospatial Reasoning framework is the most ambitious industry implementation of this paradigm. It uses Gemini to orchestrate analysis across satellite imagery, Earth Engine, BigQuery, and Google Maps data — planning and executing chains of reasoning across multiple geospatial data sources and specialized foundation models in response to natural language queries. The system doesn’t understand topology in the way a human GIS analyst does. Instead, it understands that a specific tool or model exists that handles topology, knows when to invoke it, and can interpret the results.

The LLM-Geo project from Penn State was among the first to articulate this vision as “Autonomous GIS” — an AI-powered geographic information system that leverages LLM capabilities for automatic spatial data collection, analysis, and visualization. The team has since proposed five levels of GIS autonomy, from routine-aware systems that can execute pre-defined workflows, up to knowledge-aware systems that can discover new analytical approaches. Their research agenda envisions autonomous GIS agents operating at three scales: local agents on individual machines, centralized agents serving organizations, and infrastructure-scale agents that coordinate across distributed geospatial resources.

The GIS Copilot project takes this paradigm directly into existing GIS software, embedding LLMs into QGIS to autonomously generate spatial analysis workflows. Testing across over 100 tasks of varying complexity showed high success rates for basic and intermediate operations — single-tool tasks and guided multi-step workflows — with challenges remaining in fully autonomous execution of advanced, unguided multi-step analyses.

GTChain demonstrates another facet of this approach: a fine-tuned open-source model (based on LLaMA-2-7B) trained specifically to generate chains of geospatial tool usage. Remarkably, this relatively small, domain-specialized model achieved over 32% higher accuracy than GPT-4 in solving geospatial tasks — a powerful argument that purpose-built models outperform general-purpose giants when the task is well-defined.

Benchmarking efforts like GeoBenchX and GeoAnalystBench are providing the empirical foundation for evaluating how well different models perform as tool orchestrators. GeoBenchX tested models across 202 multi-step geospatial tasks requiring buffer operations, spatial overlays, distance calculations, and specialized visualizations. The results revealed that while the best models (OpenAI’s o4-mini and Claude Sonnet 3.5) performed well overall, common errors included misunderstanding geometrical relationships, relying on outdated knowledge, and inefficient data manipulation — exactly the kinds of mistakes that a human GIS professional would catch immediately.

To make this concrete: in benchmark tasks where models were asked to determine spatial relationships between features — whether a parcel intersects a flood zone, for instance — several models incorrectly relied on textual descriptions or proximity heuristics rather than performing actual geometric intersection logic. The results looked plausible. They were wrong. In a government context, that kind of error isn’t an inconvenience — it’s a liability.

The strength of the orchestration paradigm is that it leverages decades of investment in proven, precise geoprocessing tools. When an LLM agent calls a buffer operation through arcpy or GeoPandas, the geometric computation is exact — it’s the same engine that’s been validated and relied upon for years. The model’s job is to select the right tool and parameterize it correctly, not to reinvent computational geometry.

The weakness is brittleness. Current models fail in ways that are unpredictable and sometimes invisible. They might select the wrong coordinate system for a distance calculation, misinterpret an attribute field name, or construct a workflow that executes without errors but produces spatially meaningless results. The GeoAnalystBench findings are telling: proprietary models like ChatGPT-4o-mini achieved 95% workflow validity on their benchmark, but tasks requiring deeper spatial reasoning — spatial relationship detection, optimal site selection — remained the most challenging across all models. A 95% success rate sounds impressive until you consider that in a government context, the 5% failure rate might include the legally consequential analyses.

The Convergence

In practice, the future of AI-assisted GIS will almost certainly combine both paradigms. A model needs enough internalized spatial reasoning (Paradigm 1) to understand what a spatial problem requires — to recognize that a question about proximity implies a buffer operation, that a question about “within” implies a containment test, that comparing features across layers implies an overlay. But it also needs robust tool-use capabilities (Paradigm 2) to execute those operations with computational precision through validated geoprocessing engines.

Think of it as the difference between a GIS analyst who understands spatial concepts and a GIS analyst who also knows the software. You need both. A model that can reason spatially but can’t execute operations is an armchair theorist. A model that can chain tools together but doesn’t understand why is a script that works until it encounters an edge case nobody anticipated.

For government agencies, this convergence has a practical implication: the AI systems that eventually assist their GIS workflows will be most effective when they combine a foundation of spatial understanding with precise, auditable tool execution. The spatial reasoning component helps the system interpret ambiguous natural language requests correctly. The tool orchestration component ensures the actual computation is exact, reproducible, and defensible — qualities that matter enormously when the output carries legal or regulatory weight.

The Government GIS Question

For the tens of thousands of local and state government entities in the United States that maintain GIS programs, these developments raise an immediate and practical question: will there come a day when a city planner, a public works director, or a county commissioner can simply talk to their geodatabase?

The answer is almost certainly yes. But the path from here to there is more nuanced than technology demonstrations suggest.

The Architecture Is Taking Shape

The fundamental pattern for AI-assisted government GIS already exists in pieces. An LLM doesn’t need to contain the geodatabase — it needs to be able to communicate with it. The architecture would place a natural language interface on top of an agent layer that queries an enterprise geodatabase via SQL or REST API, executes geoprocessing operations, and returns results as maps, tables, or narrative reports. The end user never opens ArcGIS Pro or QGIS — they ask questions in plain English.

This isn’t theoretical. Google’s Geospatial Reasoning framework already demonstrates this workflow at scale, using Gemini to orchestrate analysis across satellite imagery, Earth Engine, BigQuery, and Google Maps data through natural language. Esri is moving in the same direction, integrating Microsoft Azure OpenAI into ArcGIS and rolling out AI assistants across its product line. Research prototypes like GIS Copilot have demonstrated that non-experts can perform meaningful spatial analysis through natural language interaction with QGIS.

A public works director could ask, “How many miles of water main older than 50 years are in the northeast service area?” and receive an answer with an accompanying map — a query that currently requires either GIS expertise or a formal request to the GIS department. A planning director could ask, “Show me all commercially zoned parcels larger than two acres that aren’t in the floodplain” and get an instant result that currently takes a trained analyst several minutes to produce.

The Government-Specific Challenges

However, several factors unique to government operations will shape how — and how quickly — this transition occurs.

Data security is non-negotiable. Many government agencies handle law enforcement data, critical infrastructure information, utility networks, and sensitive property ownership records that cannot be transmitted to external cloud services. The question of localized LLMs — models running on agency-owned infrastructure or within FedRAMP-certified environments — is not optional for these organizations. Open-source models like Meta’s Llama and Mistral are becoming capable enough to run locally, but most county GIS shops lack the IT infrastructure and expertise to deploy and maintain a local LLM stack. This gap between what’s technically possible and what’s operationally feasible will define adoption timelines for many agencies.

Precision carries legal weight. When a GIS analyst runs a buffer analysis to determine which property owners must receive notification of a public hearing for a zoning case, that’s a legal process governed by statute. If an LLM generates a 300-foot buffer instead of the required 500-foot buffer because it misinterpreted the request, the error doesn’t just produce a wrong answer — it potentially invalidates the entire zoning decision and exposes the municipality to legal challenge. Government GIS work frequently carries regulatory or legal consequences, and the tolerance for AI errors in these contexts is effectively zero. This means human review remains in the loop far longer than in private-sector applications.

Enterprise geodatabases are more than data stores. A well-designed government enterprise geodatabase includes topology rules that enforce spatial integrity, geometric or utility networks that model connected infrastructure, versioned editing workflows that allow multiple analysts to work simultaneously, archiving systems that maintain historical records, and relationship classes that link spatial features to related tables. An LLM that can query this data is valuable. An LLM that can edit this data while respecting all of these constraints is a dramatically harder problem — and one that the research community has barely begun to address.

The data readiness gap is enormous. An LLM agent can only work effectively with a geodatabase if it understands the schema — field names, coded value domains, relationship classes, subtypes, and the actual meaning behind cryptic field names like ZONE_CD or PARCEL_STS. Most government geodatabases carry years of accumulated technical debt: inconsistent naming conventions, undocumented domains, retired fields that nobody deleted, and institutional knowledge about what certain coded values mean that exists only in the heads of long-tenured staff. Before an AI system can be useful, someone must create comprehensive metadata and data dictionaries that a model can reference. This foundational work — schema rationalization, metadata creation, domain standardization, and documentation of business rules — is the essential prerequisite for AI-assisted GIS, and most agencies haven’t done it.

Auditability, Transparency, and the Public Sector Standard

Beyond the technical challenges, government agencies face a set of governance requirements that the private sector largely does not.

Public agencies operate under open records laws. Any analysis that informs a government decision — a zoning determination, a permit approval, a resource allocation — may be subject to public records requests and legal discovery. This means AI-assisted analyses must be reproducible and explainable. A workflow that produces correct results but cannot show how it arrived at those results may be unacceptable in regulatory contexts, regardless of its accuracy.

This creates a strong argument for the tool orchestration paradigm over pure spatial reasoning, at least for government applications. When an LLM agent generates a documented sequence of geoprocessing operations — buffer this layer by 500 feet, spatially join with that layer, filter by this attribute — the workflow is auditable. Each step can be inspected, validated, and reproduced. When a model relies on internalized spatial reasoning to produce an answer directly, the reasoning process is opaque, and the result is difficult to defend in a public hearing or a courtroom.

Model transparency is another consideration. Government agencies will need to understand what models they are using, what data those models were trained on, and what the known limitations are. Esri has begun addressing this with its AI Transparency Cards initiative, which documents the capabilities, data sources, and safeguards for AI features within ArcGIS. This kind of documentation will likely become a baseline expectation for any AI system deployed in a government GIS context.

Implications for the GIS Industry

These developments do not signal the end of GIS as a discipline or the obsolescence of platforms like ArcGIS. They signal a transformation in how spatial analysis is accessed, performed, and validated.

Esri, with approximately $2 billion in annual revenue and deep institutional entrenchment across government, is adapting by positioning ArcGIS as a “GeoAI platform” — the orchestration layer where foundation models, LLM assistants, and traditional geoprocessing converge. Their partnership with Microsoft for Azure OpenAI integration, their embedding of foundation models into ArcGIS Pro, and their rollout of AI assistants across the product line demonstrate a company that recognizes the shift and is moving to stay ahead of it.

The open-source ecosystem, meanwhile, is where much of the fundamental research is happening. Projects like LLM-Geo, GIS Copilot, and various geospatial benchmarking frameworks are overwhelmingly built on QGIS, GeoPandas, and Python. Google’s Geospatial Reasoning framework represents perhaps the most ambitious effort to combine foundation models with geospatial data at planetary scale.

For GIS professionals, the message is clear: the skills that will retain their value are not the procedural knowledge of which buttons to click in which sequence. Those workflows are exactly what LLMs will learn to automate first. The enduring skills are the ones MapTrace cannot yet teach a model — understanding why a particular spatial operation is appropriate, recognizing when an AI-generated result is subtly wrong, designing geodatabases that maintain integrity over decades, and applying professional judgment to complex spatial problems where context and nuance matter.

For government agencies, the immediate action item is not deploying AI — it’s preparing for AI. That means investing in data documentation, schema rationalization, metadata standards, and the foundational geodatabase hygiene that will determine whether an AI assistant can work effectively with their data when the technology matures. The agencies that do this preparatory work now will be positioned to adopt AI-assisted workflows well ahead of those that wait.

We are entering the early stages of teaching AI to reason spatially. The question for the GIS community is not whether this transformation is coming, but whether we’ll be ready when it arrives.

Eric Pimpler is the founder of Geospatial Training Services, which has trained over 14,000 GIS professionals since 2005, and Location3x, a GIS consulting division specializing in automation, application development, and data science for government agencies.